Waiting For My Love To Find Me: Lorena Torres

Pablo’s Birthday is pleased to present Lorena Torres: Waiting For My Love to Find Me. This will be the artist’s inaugural solo exhibition at the gallery and in the United States. Through her artistic process, Torres arrived at the realization that she was illustrating the idea of falling in love, and the paintings carry on her visual inquiry with fleeting concurrences on this very tender theme. The exhibition explores the artist’s ongoing narrative with twelve new oil paintings depicting the faces, figures, and scenes, of hesitant and passing moments.

Waiting For My Love to Find Me began with a poem of the same title that Torres composed after a period of loneliness and contemplation. She describes the scenes, that are set in her home in Colombia, as formed by a perspective that has distanced and cooled beyond a previous infatuation. They mark transient moments that fit into a broader story on love and its eventual endings. This dissipated love has come, and the end is apparent, so now is the time to await the next. Torres’ poem is modeled after Sylvia Plath’s Mad Girl’s Love Song where the line “(I think I made you up inside my head.)” is a recurrent verse. The story in these paintings calls to this foregone love that now feels trite or pedestrian, or even routine and mundane. Perhaps it never happened at all, or perhaps the lovers wish it didn’t.

Through the images, Torres has formed a temporal framework so that love both encountered or misencountered is on display. While the show presents an overall chronological narrative, the impermanence of the moments portrays a poignant and emotional stance towards the love that was there. With deadpan humor, Que solo nos quede esto (only this is left for us) (2023) indicates something almost indescribable, leftover from a vanishing moment of prosperity or abundance. That something is the white bougainvillea, which is depicted between the two women and is held in one of their hands. Their vestiges are also adorned with the ubiquitous flower. Chao, mi amor (Goodbye, my love) (2023) shows a man against a red background and two lean trees on either side of him. His eyes are closed and he is posing with arms outstretched, hands extended, and one leg slightly bent at the knee. The farewell seems saturated with an unwillingness.

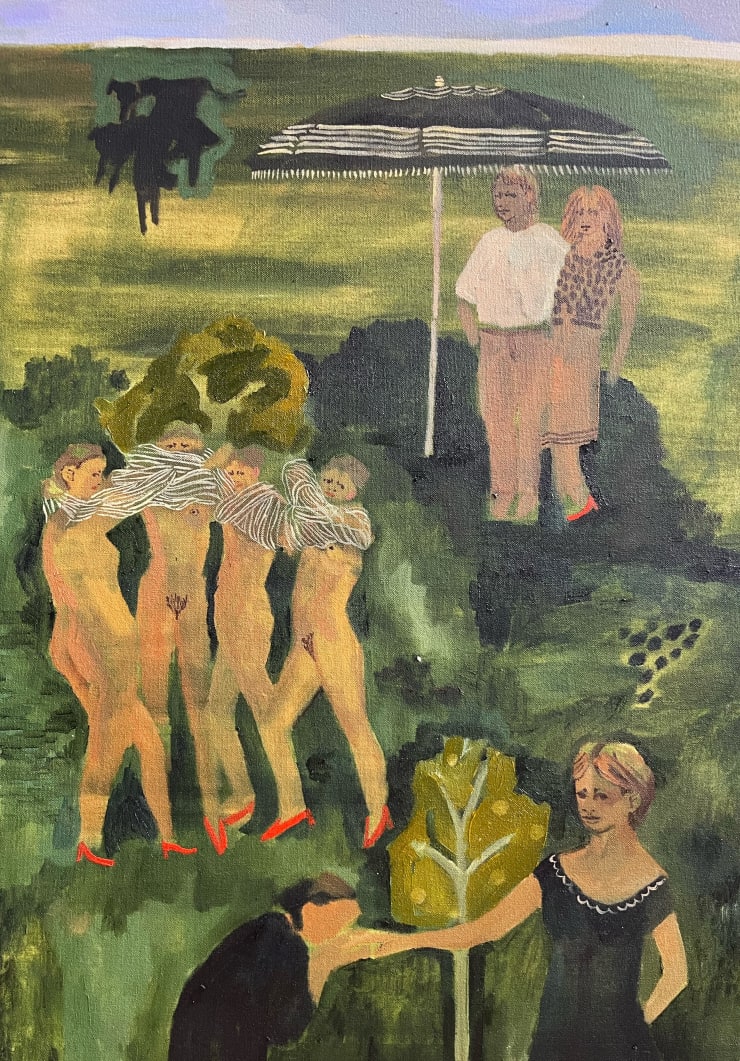

As the exhibition delves into the attachments and lingering feelings from a prior experience, it also communicates the difficulties of finding one’s way. Dar gracias a las amigas por sus consejos que nunca sigo (Thanks to friends for their advice that I never follow) (2023) depicts a woman with red shoes levitated above a table that are perhaps her friends or family. In Todo aquello que nos separa (All that separates us) (2023), Torres illustrates a man and a woman standing under an umbrella, an assembly of four women with arms above their head all tied together with twine with a tree behind them, and a man kneeling and kissing a woman’s hand in the bottom right corner also with a tree in the background. The scenes are somewhat deconstructed and disparate or broken away from a linear narrative.

The setting is placed in what appears to be the Colombian countryside in a style like Gauguin’s Breton Girls Dancing Pont-Aven (1888), where the backdrop is as important to the sentiment of the work as the figures themselves. The context creates the stage for Torres to engage with what she calls a wordless dialogue with the primitivism of the region. Her scenes do not necessarily speak to a cultural affirmation of “Colombian” or “South American” as it does to the space or the visual cues created by her close-knit family life and therefore her own comfort in the symbolism of nature and her surroundings. This represents a reclamation of her coastal Caribbean home. Further to the context of place, Torres prolifically employs the bougainvillea flower. Even in her earlier work, this flower is profoundly present. Her illustration of the flower indicates a record of her personal experience with its long existence, and therefore importance as a symbol, in her life.

While employing soft painterly brushstrokes to create imagery caught in the hazy slow motion of a dream, Torres sets the tone with an intimate collective history. The work indicates the artist’s bearing of rural places where she feels most at home. This comes from a desire and need to connect with a feeling of belonging to a place and a world. However, they are more than a perspective view into the pastoral, the homely and coy. They show the artist's ability to bring to life the seemingly surreal.

Text by Katelynn Dunn.